About insomnia

yes, i kinda have this sleeplessness problem for 2 years. This is getting worse sicne I gott Manchester. It'll make sense if I say it's the jet lag that I have problem with, bugt I've been in Europe for like 2 weeks. Doensn't make sense, anyway.

I was so excited of solving registration problem with MMU ID today, went to the library, made ID card and then 30 mins later, I was dozing in the sofa of library. What am I doing in Manchester!!!!!

2011-09-29

2011-09-28

27th Sept, 2011

27th Sept, 2011

a Flat tire of my damn new second-used bike

Olive

Greek Friend

Lack of Sleepness

Enlgish?? Why is it so difficult?

Getting refund of swimming pool

a Flat tire of my damn new second-used bike

Olive

Greek Friend

Lack of Sleepness

Enlgish?? Why is it so difficult?

Getting refund of swimming pool

2011-09-25

Hot Chelle Rae - Tonight, Tonight

"Tonight, Tonight"

It’s been a really really messed up week

Seven days of torture, seven days of bitter

And my girlfriend went and cheated on me

She’s a California dime but it’s time for me to quit her

★ La la la, whatever, la la la, it doesn’t matter, la la la, oh well, la la la

We’re going at it tonight tonight

There’s a party on the rooftop top of the world

Tonight tonight and were dancing on the edge of the Hollywood sign

I don’t know if I’ll make it but watch how good I’ll fake it

It's all right, all right, tonight, tonight

I woke up with a strange tattoo

Not sure how I got it, not a dollar in my pocket

And it kinda looks just like you

Mixed with Zach Galifianakis

★

You got me singing like

Woah, come on, ohh, it doesn’t matter, woah, everybody now, ohh

Just don’t stop let’s keep the beat pumpin’

Keep the beat up, lets drop the beat down

It’s my party dance if I want to

We can get crazy let it all out (x2)

Its you and me and were runnin this town

And its me and you and were shakin the ground

And ain’t nobody gonna tell us to go cause this is our show

Everybody

Woah, come on, ohh, all you animals

Woah, let me hear you now, ohh

Tonight tonight there’s a party on the rooftop top of the world

Tonight tonight and were dancing on the edge of the Hollywood sign

I don’t know if I’ll make it but watch how good I’ll fake it

Its all right, all right, tonight, tonight

Its all right, all right, tonight, tonight

Yeah its all right, all right, tonight, tonight

Just singing like

Woah, come on, ohh, all you party people

Woah, all you singletons, ohh, even the white kids

Just don’t stop lets keep the beat pumpin’

Keep the beat up, lets drop the beat down

Its my party dance if I want to

We can get crazy let it all out (x2)

2011-09-23

Internet of Things

Volume # 28: Internet of Things

Bookmark

This issue of Volume explores architects’ roles in the age of the internet. For us at ArchDaily, this is a topic we find very interesting. We ask all the architects we interview how the internet has changed their practice; their answers nicely complement this issue. (You can check them out in our interview section). I, personally, enjoyed the section titled “Tracing Concepts.” It illustrates the influence design ideas have had on the computing world and vise versa. For example, it details how Christopher Alexander’s ideas about design patterns has spurred on object-oriented programming and bottom-up design solutions.

Content:

2 Editorial / Arjen Oosterman

5 The Common Sense / Mark Shepard interviewed by Vincent Schipper

8 Parallel Universe / Stephen Gage

10 Touching the Interspace / Carola Moujan

14 The Devil is in the Details: Critical Knowledge About Emerging Information Technologies / Shintaro Myazaki

16 Noo-Architecture & the Internet of Things / Deborah Hauptmann

20 An Axis of Innumerable Connections: The Mundaneum / Nina Larsen

25 Tracing Concepts / Edwin Gardner and Marcell Mars Insert

49 Smart Environments / Ken Sakamura interviewed by Cloud Lab

52 Revisiting Yesterday’s Future: the 1960s and the Internet of Things / Lara Schrijver

56 Architecture as a Multi-Agent System / Tomasz Jaskiewicz

61 The City is Becoming / Ben Cerveny, James Burke, Juha van’t Zelfde

66 Play Design / Ben Schouten

70 Check-In Urbanism / Jeroen Beekmans and Joop de Boer

72 Hylozoic Ground / Philip Beesley

80 Being Somewhere / Ole Bouman

81 Trust Design – Part Two: Internet of Things / Insert

121 Permission Taken for Granted / Bart-Jan Polman

124 The Importance of Random Learning / Hiroshi Ishiguro interviewed by Cloud Lab

128 Shadow Project / Nortd Labs

130 The Color of Ideas / Tuur van Balen

134 Meeting the Middle / Ruairi Glynn interviewed by Vincent Schipper

138 Virt-Oral History: A Story from Seven on Seven / Justin Fowler

140 All That is material Will Be Standard and All that Is Personalized Will Be Virtual / Eduard Sansho Pou

142 The Tragic Lost / Vincent Schipper and Christiaan Fruneaux

148 The Act of Disconnection: Just Because I Do Not Send a Message within a Matter of Minutes Does Not Mean I Am Dead / Amelia Borg and Timothy Moore

152 Unlocking the Secrets of a ‘Forbidden City’ / Lorna Goulden

155 21st Century City

156 Data and Owner / Usman Haque and Ed Borden

158 Digital-Material Practices: Adaptive Architecture for an Idealization of the Soft / Mette Ramsgard Thomsen

162 Res Sapiens / Dimitri Nieuwenhuizen

166 Urban Content / Mark Dek

169 IOOO – the Internet of Obsolete Objects / Dietmar Offenhuber

172 Coders & Architects Do Not Communicate / Vincent Schipper

174 Losing Ground / Arjen Oosterman

176 Colophon

Editor: Arjen Oosterman

You can subscribe here

http://www.archdaily.com/166963/volume-28-internet-of-things/

2011-09-21

2011-09-19

Bibliotheque Nationale

| Architect | Henri Labrouste |

Subscribers - login to skip ads |

| Location | Paris, France map | |

| Date | 1862 to 1868 timeline | |

| Building Type | central library | |

| Construction System | bearing masonry, iron columns, terra cotta vaults, truss roof | |

| Climate | temperate | |

| Context | urban | |

| Style | Neoclassical | |

| Notes | Original scheme by Etienne-Louis Boullee, 1785. |

"The Reading Room is covered with a series of nine pendentived simple domes of terra-cotta, supported by twelve slender columns of iron, aranged in four rows, the outer columns standing close to the walls."

— Sir Bannister Fletcher, A History of Architecture, p1206.

2011-09-18

A Daily Dose of Architecture: Today's archidose #498

A Daily Dose of Architecture: Today's archidose #498: The Royal Observatory , originally uploaded by fairminer . The Peter Harrison Planetarium at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London,...

2011-09-17

Pompidou centre

The nuts and bolts of the hi-tech age

High-tech architecture emerged in the 1970s. The term was first coined in a book: High Tech: The Industrial Style and Source Book for The Home, by Joan Kron and Suzanne Slesin, in which the architectural style is characterised by a "nuts-and-bolts, exposed-pipes, technological look". The Pompidou Centre is the building that epitomises it. It broke the mould with its rebellious all-exposed construction: the steel structure from which the floors are suspended is visible from the outside, as are the giant external escalators, and the service ducts - colour-coded yellow for electricity, red for heating, blue for air and green for water. High-tech brought a refreshing new face to modern architecture, which was becoming increasingly associated with brutalist slabs encased in grimy concrete, and the bad press they received for their failings. Science and technology were having a major impact on society - the memory of the Apollo moon landings was still fresh - and there was a feeling that with the right technology anything was possible. Architecture, too, was having its techno moment, as traditional construction gave way to space frames with metal and glass cladding, and extensive use of factory-produced materials and components. The pioneers of this style - Rogers and Piano, Norman Foster, Michael Hopkins - created an architectural language that, by externalising its technical elements and allowing them to create the building's facade, gave modernism a new lease on life when it most needed it. Henrietta Thompson

Operating under the influence

The inside-out gallery and performance centre in Paris' Beaubourg is named after former French president Georges Pompidou, but its development was closely followed by his wife, Claude. It is rumoured that Georges Pompidou did not approve of the jury's choice of architects and would have preferred a more classical approach. But the couple were passionate collectors of contemporary art - Claude had a particularly interest in the work of Yves Klein - and it was claimed that the permanent collection for the centre was based largely on Claude's knowledge of her husband's taste. Whether Georges would have approved of the selection is open to speculation as he died three years before the building was unveiled in 1977. Noted for her love of fashion as much as her interest in modern art, the publicity-shy Claude did not enjoy political life, once famously describing the Élysée Palace a "house of sadness". It was her influence that saw the couple redecorate the palace with daring contemporary designs including painted aluminium walls and furniture by Pierre Paulin. HT

70s flair gives way to 90s pragmatism

Some things must have seemed like a good idea at the time. The Centre Georges Pompidou, designed by Rogers and Piano together with structural engineer Peter Rice, was devised using a supremely flexible structural system to allow for deep, unencumbered exhibition spaces. The distinctive colour-coded service ducts were banished to the exterior, where, it must be said, they deteriorated swiftly in the grimy Parisian atmosphere. Originally designed for 5,000 visitors a day, the Pompidou was groaning under five times that number, traipsing through the galleries and expansive public foyers. Fixtures and finishes were showing their age, while the steel frame also needed a wash and a brush up, having weathered and rusted badly. At the end of 1997 a major restoration programme began, budgeted at around €135m. The job was overseen by Renzo Piano - without Rogers - along with the French architect Jean-François Bodin. Interior spaces were re-jigged, new escalators installed, and a certain amount of "flexibility" removed in order to create a more functional space. The dream of the modular building died, along with the public-spirited, free access to the roof via the snaking glass-enclosed escalators - much to Rogers' disappointment. Jonathan Bell

A Pompidou Centre for all seasons

The second Pompidou Centre, scheduled to open 2008, will, according to its architects, provide "a new type of public institution that can grow and transform itself according to climate or occasion". France's first Pompidou Centre outside Paris will open in the city of Metz, in the Lorraine region, and has been designed by the Japanese Shigeru Ban Architects in association with Jean de Gastines (Paris) and Gumuchdjian Architects (London). Shigeru Ban - who beat off tough competition from others including Foreign Office Architects and Herzog & de Meuron - is best-known for his innovative work with paper, particularly recycled cardboard tubes, which he has used to house disaster victims. The new building is a modular structure, designed around a central 77m-high spire. Three rectangular cantilevered tubes will form the galleries for the permanent collections and will be angled to frame views of the city's historic monuments. The most dramatic feature of the new Centre will be the roof - inspired by a Muak Kui, the woven bamboo Chinese hat. Draped over the entire complex like a massive translucent, hexagonal, lattice sheet, the roof will protect the facades from cold northerly winds in winter and provide shade in the summer. HT

Here comes the fun with the Fab Six

What were they thinking? The psychedelic cartoon architecture of the Pompidou Centre had its roots in the work of avant garde architecture group Archigram, sometimes known as "architecture's Beatles". Archigram's playful, twisty-pop visions of a technocratic future had grabbed headlines after its formation in 1961 by a group of young London architects - Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron and Michael Webb. Frustrated with the intellectual conservatism of the British architectural establishment, the fab six mixed pop art's fascination with found objects with new (and hypothetical) technology to imagine a new type of architecture. In 1962, Chalk, Crompton and Herron were invited to produce an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London; the result was Living City, a manifesto for their belief "in the city as a unique organism", not just a collection of buildings, but a means of empowering people to choose how to lead their lives. Memorable projects include Ron Herron's 1964 cartoon of a Walking City in which giant, reptilian structures glided across the world on enormous legs until its inhabitants wanted to settle; and Peter Cook's 1964 Plug-in City, involving crane-mounted living pods that could be plugged in wherever convenient. In 1968, the group proposed an Instant City that would fly from place to place and temporarily "land" in small communities - letting the inhabitants enjoy the buzz of city life without having to go there themselves. Archigram's influence on the Pompidou Centre is obvious, although some Archigram members were apparently disappointed that it didn't move. HT

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2007/oct/09/architecture2

High-tech architecture emerged in the 1970s. The term was first coined in a book: High Tech: The Industrial Style and Source Book for The Home, by Joan Kron and Suzanne Slesin, in which the architectural style is characterised by a "nuts-and-bolts, exposed-pipes, technological look". The Pompidou Centre is the building that epitomises it. It broke the mould with its rebellious all-exposed construction: the steel structure from which the floors are suspended is visible from the outside, as are the giant external escalators, and the service ducts - colour-coded yellow for electricity, red for heating, blue for air and green for water. High-tech brought a refreshing new face to modern architecture, which was becoming increasingly associated with brutalist slabs encased in grimy concrete, and the bad press they received for their failings. Science and technology were having a major impact on society - the memory of the Apollo moon landings was still fresh - and there was a feeling that with the right technology anything was possible. Architecture, too, was having its techno moment, as traditional construction gave way to space frames with metal and glass cladding, and extensive use of factory-produced materials and components. The pioneers of this style - Rogers and Piano, Norman Foster, Michael Hopkins - created an architectural language that, by externalising its technical elements and allowing them to create the building's facade, gave modernism a new lease on life when it most needed it. Henrietta Thompson

Operating under the influence

The inside-out gallery and performance centre in Paris' Beaubourg is named after former French president Georges Pompidou, but its development was closely followed by his wife, Claude. It is rumoured that Georges Pompidou did not approve of the jury's choice of architects and would have preferred a more classical approach. But the couple were passionate collectors of contemporary art - Claude had a particularly interest in the work of Yves Klein - and it was claimed that the permanent collection for the centre was based largely on Claude's knowledge of her husband's taste. Whether Georges would have approved of the selection is open to speculation as he died three years before the building was unveiled in 1977. Noted for her love of fashion as much as her interest in modern art, the publicity-shy Claude did not enjoy political life, once famously describing the Élysée Palace a "house of sadness". It was her influence that saw the couple redecorate the palace with daring contemporary designs including painted aluminium walls and furniture by Pierre Paulin. HT

70s flair gives way to 90s pragmatism

Some things must have seemed like a good idea at the time. The Centre Georges Pompidou, designed by Rogers and Piano together with structural engineer Peter Rice, was devised using a supremely flexible structural system to allow for deep, unencumbered exhibition spaces. The distinctive colour-coded service ducts were banished to the exterior, where, it must be said, they deteriorated swiftly in the grimy Parisian atmosphere. Originally designed for 5,000 visitors a day, the Pompidou was groaning under five times that number, traipsing through the galleries and expansive public foyers. Fixtures and finishes were showing their age, while the steel frame also needed a wash and a brush up, having weathered and rusted badly. At the end of 1997 a major restoration programme began, budgeted at around €135m. The job was overseen by Renzo Piano - without Rogers - along with the French architect Jean-François Bodin. Interior spaces were re-jigged, new escalators installed, and a certain amount of "flexibility" removed in order to create a more functional space. The dream of the modular building died, along with the public-spirited, free access to the roof via the snaking glass-enclosed escalators - much to Rogers' disappointment. Jonathan Bell

A Pompidou Centre for all seasons

The second Pompidou Centre, scheduled to open 2008, will, according to its architects, provide "a new type of public institution that can grow and transform itself according to climate or occasion". France's first Pompidou Centre outside Paris will open in the city of Metz, in the Lorraine region, and has been designed by the Japanese Shigeru Ban Architects in association with Jean de Gastines (Paris) and Gumuchdjian Architects (London). Shigeru Ban - who beat off tough competition from others including Foreign Office Architects and Herzog & de Meuron - is best-known for his innovative work with paper, particularly recycled cardboard tubes, which he has used to house disaster victims. The new building is a modular structure, designed around a central 77m-high spire. Three rectangular cantilevered tubes will form the galleries for the permanent collections and will be angled to frame views of the city's historic monuments. The most dramatic feature of the new Centre will be the roof - inspired by a Muak Kui, the woven bamboo Chinese hat. Draped over the entire complex like a massive translucent, hexagonal, lattice sheet, the roof will protect the facades from cold northerly winds in winter and provide shade in the summer. HT

Here comes the fun with the Fab Six

What were they thinking? The psychedelic cartoon architecture of the Pompidou Centre had its roots in the work of avant garde architecture group Archigram, sometimes known as "architecture's Beatles". Archigram's playful, twisty-pop visions of a technocratic future had grabbed headlines after its formation in 1961 by a group of young London architects - Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron and Michael Webb. Frustrated with the intellectual conservatism of the British architectural establishment, the fab six mixed pop art's fascination with found objects with new (and hypothetical) technology to imagine a new type of architecture. In 1962, Chalk, Crompton and Herron were invited to produce an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London; the result was Living City, a manifesto for their belief "in the city as a unique organism", not just a collection of buildings, but a means of empowering people to choose how to lead their lives. Memorable projects include Ron Herron's 1964 cartoon of a Walking City in which giant, reptilian structures glided across the world on enormous legs until its inhabitants wanted to settle; and Peter Cook's 1964 Plug-in City, involving crane-mounted living pods that could be plugged in wherever convenient. In 1968, the group proposed an Instant City that would fly from place to place and temporarily "land" in small communities - letting the inhabitants enjoy the buzz of city life without having to go there themselves. Archigram's influence on the Pompidou Centre is obvious, although some Archigram members were apparently disappointed that it didn't move. HT

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2007/oct/09/architecture2

A Blooming Cuppa Tea

A Blooming Cuppa Tea

2011-09-16

Church at Firminy / Le Corbusier

archidaily

Architect: Le Corbusier

Location: Firminy, France

Project Year: 1963

Photographs: Richard Weil, Wikimedia Commons

References: Le Corbusier, Michael Raeburn

Architect: Le Corbusier

Location: Firminy, France

Project Year: 1963

Photographs: Richard Weil, Wikimedia Commons

References: Le Corbusier, Michael Raeburn

Église de la Madeleine

L'Eglise de la Madeleine :

L'église de la Madeleine, or L'église Sainte-Marie-Madeleine (or simply "La Madeleine"), is a church in the 8th arrondissement of Paris that was designed as a temple to the glory of Napoleon's army.

History

Three false starts were made on building a church on this site. The first design, commissioned in 1757 with construction begun in 1764, was by Pierre Contant d'Ivry, and was based on Mansart's Late Baroque church of Les Invalides, with a dome surmounting a Latin cross. In 1777 d'Ivry died and he was replaced by Guillaume-Martin Couture, who decided to start anew, razing the incomplete construction and basing his new design on the Pantheon. At the start of the Revolution, only the foundations had been finished and work was discontinued, while debate simmered as to what purpose the building might serve in Revolutionary France: a library, a ballroom, and a marketplace were all suggested.

In 1806 Napoleon made his decision, commissioning Pierre-Alexandre Barthélémy Vignon (1763-1828) to build a Temple de la Gloire de la Grande Armée (Temple to the Glory of the Great Army), with Vignon basing his design on an antique temple. The then-existing foundations were razed and work begun anew. With completion of the Arc de Triomphe in 1808, the original commemorative role for the temple was blunted. After the fall of Napoleon, with the Catholic reaction during the Restoration, King Louis XVIII determined that the structure would be used as a church. Vignon died in 1828 before completing the project and was replaced by Jacques-Marie Huvé. In 1837 it was briefly suggested that the building might best be utilized as a train station, but the building was finally consecrated as a church in 1842.

Architecture

Interior of the Église de la Madeleine, ParisThe Madeleine is built in the Neo-Classical style and was inspired by the Maison Carrée at Nimes, the best-preserved of all Roman temples. Its 52 Corinthian columns, each 20 metres high, are carried around the entire exterior of the building. The pediment is adorned by a sculpture of the Last Judgement by Lemaire, and the church's bronze doors bear reliefs representing the Ten Commandments.

Inside, the church has a single nave with three domes, lavishly gilded in a decor inspired by Renaissance artists. At the rear of the church, above the high altar, stands a statue by Charles Marochetti depicting St Mary Magdalene being carried up to heaven by two angels. The half-dome above the altar is covered with a fresco by Jules-Claude Ziegler, entitled The History of Christianity, showing the key figures in the Christian religion with - perhaps inevitably - Napoleon occupying centre stage.

The Madeleine today

The Madeleine is affiliated with a Benedictine abbey, and masses and the most fashionable weddings in Paris are still celebrated here.

The church has a celebrated pipe organ, built by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1811-1899), which is widely regarded as one of the best in Paris. The composers Camille Saint-Saëns and Gabriel Fauré were both organists at the Madeleine, and the funerals of Frédéric Chopin and Fauré were held there.

To its south lies the Place de la Concorde, and to the east is the Place Vendôme.

wikidepia

MMMbop - hanson

MMMbop - hanson

You have so many relationships in this life

Only one or two will last

You go through all this pain and strife

Then you turn your back and they're gone so fast

And they're gone so fast

So hold on to the ones who really care

In the end they'll be the only ones there

When you get old and start losing your hair

Can you tell me who will still care?

Can you tell me who will still care?

Chorus:

Mmm bop, ba duba dop

Ba du bop, ba duba dop

Ba du bop, ba duba dop

Ba du

Mmm bop, ba duba dop

Ba du bop, Ba du dop

Ba du bop, Ba du dop

Ba du

Plant a seed, plant a flower, plant a rose

You can plant any one of those

Keep planting to find out which one grows

It's a secret no one knows

It's a secret no one knows

no one knows

(Repeat Chorus)

In an mmm bop they're gone.

In an mmm bop they're not there.

In an mmm bop they're gone.

In an mmm bop they're not there.

Until you lose your hair. But you don't care.

(Repeat Chorus)

Can you tell me? You say you can but you don't know.

Can you tell me which flower's going to grow?

Can you tell me if it's going to be a daisy or a rose?

Can you tell me which flower's going to grow?

Can you tell me? You say you can but you don't know.

(Repeat Chorus)

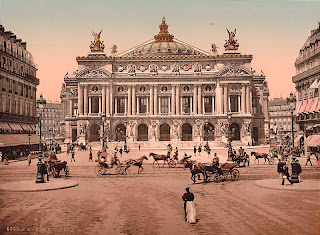

opera house, paris

Charles Garnier(1825-1898), 1861-1874

당시 프랑스는 식민지를 아프리카와 아시아까지 확장햇다.

Discussion

"Although described by a contemporary critic as 'looking like an overloaded sideboard', it (the Paris Opera House) is now regarded as one of the masterpieces of the period. Here Garnier triumphed over a cramped and difficult site, handling the carriage-ramps and approach steps, the foyers and staircases, both in section and plan, with confidence and skill. The style is monumental, classically based and opulently expressed, as the times demanded, in an elaborate language of multicoloured marbles and lavish statuary. Throughout his life, Garnier was criticized for his excessive use of ornament, as Napoleon and Haussman are still accused of being inspired by an out-of-date and imperialist showmanship expressed in a language already debased. Such critics forget that every city needs its occasional monuments and occasions of grandeur, and that thanks largely to these three men, Paris remains one of the most beautiful cities in the world."

— John Julius Norwich, ed. Great Architecture of the World. p214.

Details

The Garnier Opera is a grand landmark at the north terminus of the Av. de la Opera in Paris.

http://www.greatbuildings.com/buildings/Paris_Opera.html

2011-09-15

Théâtre Gallo-Romain

Haven't been the museum right next to it.

I do not have much information of this, also. Is there anyone who owns it?

2011-08-21

광장 (Squares of Europe, Squares for Europe)

현대 도시는 시민이 자유롭게 공통 관심사를 표현할 수 있는 새로운 광장과 공공 공간을 필요로 한다. 이는 광장의 생성을 유도하는 활동과 프로그램에 주의를 기울이고 광장이 없던 곳에 광장을 처방하는 설계를 제안해 교훈을 얻는 일이 중요한 이유이다. 주의를 더 기울이면 오늘날 많은 도시의 공공 공간의 절규를 희미하게나마 들을 수 있을 것이다. 광장 없이 도시가 있을 수 없기 때문이다.

91쪽, 광장 없이 도시도 없다 중에서

광장은 연결되어 있거나, 계획적으로 분리되어 있거나, 의도적으로 인접되어 있는 크고 작은 공간들의 집합체의 한 부분이다. 광장의 형태는 유기적이어서 그러한 관점에서 도시의 형태에 순응한다. 만약 도시가 연속된 규칙적인 조직으로 이루어져 있다면 광장 역시 완전히 새롭게 건설된 도시처럼 규칙적일 것이다. 그러나 중세의 도시처럼 도시 조직이 불규칙하다면 광장은 대지의 원래 배치형태에 순응함으로써 기하학적인 경직성에서 벗어날 것이다.

19쪽, 서론 중에서

도시 광장은 또한 도시민의 일상적 의식에서도 중요한 역할을 한다. 광장은 사람들의 가치로 채워진 공간이므로 사회적 행위가 벌어지는 무대가 되며, 광장이라는 공간에 참여함으로써 사회적 지위가 확고해진다. 이에 대한 훌륭한 예는 거주자의 사회적 지위를 암시하는 ‘주소’의 가치에서 찾아볼 수 있다. 유럽 문화의 맥락에서 주소의 가치는 주 광장에 가까울수록 크며 주소가 주 광장 근처인 사람은 그 사회에서 높은 계층에 속한다. 이런 식으로 광장은 도시 내부의 거리를 따라 기초적 공간요소가 구성되고 도시 내부의 지리적 분포가 구축되는 것에 관여한다.

광장 주변의 거리가 그 도시의 주 가로망이 되면 광장은 사람이 모이고 만나는 ‘장소’로 공식 인정된다. 아고라 같은 광장의 대중 전용 공간에서 일어나는 만남들로 말미암아 자유 연설 같은 민주주의의 이상이 실질적으로 달성된다.

61쪽, 광장과 정치 이데올로기 중에서

91쪽, 광장 없이 도시도 없다 중에서

광장은 연결되어 있거나, 계획적으로 분리되어 있거나, 의도적으로 인접되어 있는 크고 작은 공간들의 집합체의 한 부분이다. 광장의 형태는 유기적이어서 그러한 관점에서 도시의 형태에 순응한다. 만약 도시가 연속된 규칙적인 조직으로 이루어져 있다면 광장 역시 완전히 새롭게 건설된 도시처럼 규칙적일 것이다. 그러나 중세의 도시처럼 도시 조직이 불규칙하다면 광장은 대지의 원래 배치형태에 순응함으로써 기하학적인 경직성에서 벗어날 것이다.

19쪽, 서론 중에서

도시 광장은 또한 도시민의 일상적 의식에서도 중요한 역할을 한다. 광장은 사람들의 가치로 채워진 공간이므로 사회적 행위가 벌어지는 무대가 되며, 광장이라는 공간에 참여함으로써 사회적 지위가 확고해진다. 이에 대한 훌륭한 예는 거주자의 사회적 지위를 암시하는 ‘주소’의 가치에서 찾아볼 수 있다. 유럽 문화의 맥락에서 주소의 가치는 주 광장에 가까울수록 크며 주소가 주 광장 근처인 사람은 그 사회에서 높은 계층에 속한다. 이런 식으로 광장은 도시 내부의 거리를 따라 기초적 공간요소가 구성되고 도시 내부의 지리적 분포가 구축되는 것에 관여한다.

광장 주변의 거리가 그 도시의 주 가로망이 되면 광장은 사람이 모이고 만나는 ‘장소’로 공식 인정된다. 아고라 같은 광장의 대중 전용 공간에서 일어나는 만남들로 말미암아 자유 연설 같은 민주주의의 이상이 실질적으로 달성된다.

61쪽, 광장과 정치 이데올로기 중에서

2011-08-14

피드 구독하기:

덧글 (Atom)